The joke might be Okay, so, five productivity frameworks walk into a kanban board…They don’t agree on much, but their arguments might be more useful than their advice.

People are even more messed up than when we started the Personal Kanban movement 17 years ago. The need has not abated. People are overloaded, stressed, and looking for a way out. They keep finding models and falling in and out of love with them. So, as we relaunch the Personal Kanban site for a new era, it’s time to find the right way to work.

So there are a lot of productivity thinkers out there. Maybe you read David Allen and spent a weekend building a GTD setup with nested contexts and a Someday/Maybe list that runs three pages long. Maybe you read Cal Newport and time-blocked your calendar into a mosaic of deep work sessions. Maybe you tried Stephen Covey’s quadrants and felt virtuous for a while and then swallowed up by the urgent.

And maybe, somewhere in there, you discovered Personal Kanban with our two rules, a board, and the deceptively simple instruction to visualize your work and limit your work in progress.

From the beginning we wanted to make it clear that Personal Kanban was never competing with those systems, or anything else. Work changes over time, our focuses change over time. For us, PK is just a surface where their best ideas, and your best potential becomes visible, and where the contradictions between different ways of working become useful and no longer contradictions, but just serving different needs at different times.

We don’t want one framework for how we work, individuals or teams. We do, though, want to draw from the tensions between these ways of working: Allen’s “capture everything” against Newport’s “eliminate the shallow.” Covey’s top-down values against Ohno’s bottom-up waste elimination. Csikszentmihalyi’s need for total immersion against Allen’s need for constant system maintenance. We want the power of all five.

So I’m going to put Personal Kanban under these five lenses and see what each one reveals, where there are disagreements, and make something completely new.

Lens 1: David Allen’s Open Loops

David Allen’s GTD system is built on the notion that your brain is terrible at storage but excellent at processing. Every commitment without a defined next action, what Allen calls an “open loop,” occupies mental RAM, creating a low-grade anxiety that saps your capacity to focus on anything.

In the Allen world a Personal Kanban board is a powerful capture and clarification tool. The backlog column is essentially his “In” tray. The act of writing a sticky note forces the kind of processing GTD demands. We ask what is this thing, and what’s the next physical action?

Allen would want every card to answer his clarifying questions. Not just the task “Website redesign” sitting in your Doing column, but what specifically? “Draft homepage wireframe” with a context (@computer) and a time horizon. As the Personal Kanban blog explored in Paul Eastbrook’s GTD & Kanban: Similarities, Differences & Synergies series, “For GTD, it’s not about writing lists of goals: ‘buy milk’, ‘fill in tax return’, but rather, GTD is concerned with determining the next action required and given the right context or time, just performing that action without having to constantly figure out the next step each time.”

Even more power of the Allen lens is the organizing the PK backlog. Your PK backlog isn’t a guilt-inducing inventory of everything you haven’t done. Allen would insist on regular processing. Clarifying every new item and removing every non-actionable one, He would do a weekly review that keeps the board pruned.

The Focus of This Lens: Personal Kanban gives GTD the visual feedback loop it desperately needs. Allen’s system can become invisible, buried in lists and apps and folders. A board on your wall or digital keeps your commitments in your peripheral vision. But without some of Allen’s processing rigor, a kanban board becomes a graveyard of vague intentions.

Lens 2: Stephen Covey’s Ignored Quadrant

Stephen Covey would take one look at most personal kanban boards and ask a question that makes people uncomfortable: Is any of this important?

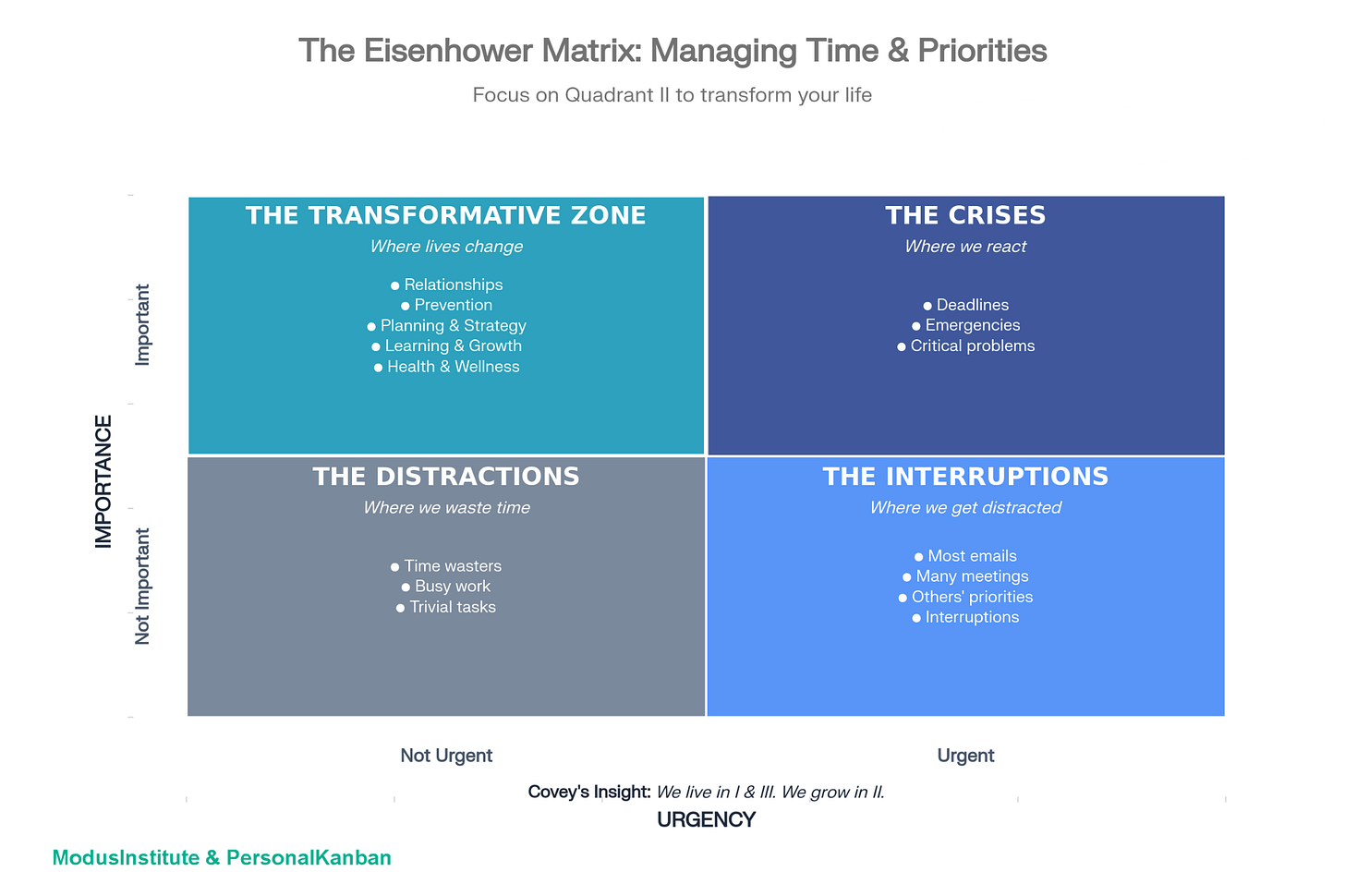

I use his (Eisenhower’s) Urgent/Important matrix as four quadrants with one life-changing insight…we spend most of our time distracted by the loudest tasks (the ones that yell and scream) and ignore the more important tasks (the ones that avoid yelling and screaming).

Covey says we spend most of our time in Quadrant I (urgent and important. The crises) and Quadrant III (urgent but not important. The interruptions). The work that actually changes our lives sits in Quadrant II: important but not urgent. This is where relationships, prevention, planning, and learning wait (im)patiently for the chaos to die down. And the longer it is forgotten, the more loud work becomes.

Covey would see kanban’s visualization as powerful but incomplete without a values layer. A board full of urgent tasks moving smoothly from Backlog to Doing to Done isn’t productivity — it might be efficient motion toward the wrong destination. “Begin with the end in mind” means every card should trace back to a role you’ve chosen and a mission you’ve defined.

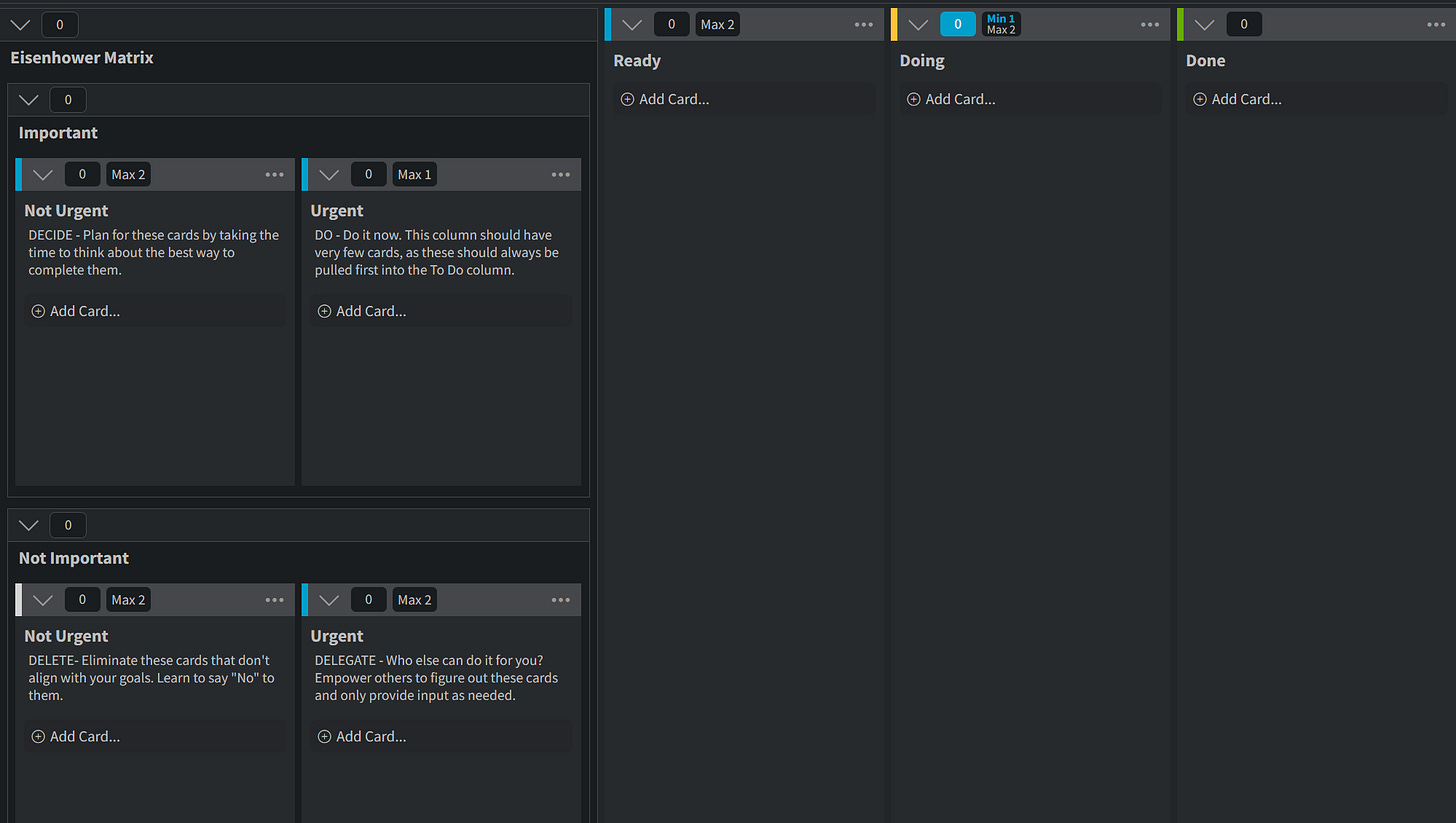

This is where Covey’s lens gets practical. In Personal Kanban, the Priority Filter can essentially be Covey’s quadrants applied to a board. Or you can create an urgent and important matrix in your own board. Before pulling work into your Doing column, run it through a filter that makes you ask…is this urgent, important, both, or neither? The pattern doesn’t just organize tasks. It forces a conversation with yourself about what is the best use of your time right now and in the future.

Here we have some tension between Covey and Ohno (we’ll get to him). This could be one of the most productive in all of productivity thinking. Covey says: start with your values, then design your work. Ohno says: start with your work, then eliminate what doesn’t belong. Top-down or bottom-up? The answer might be both (and Personal Kanban’s mission-based approach shows what that looks like).

The Focus of This Lens: Visualization without prioritization is just a prettier (uglier) to-do list. Covey pushes kanban practitioners to add values or purpose, not just what you’re doing, but why it should even be done and whether it connects to the person you’re trying to become.

Lens 3: Cal Newport Blowing Up Your Productivity System

Cal Newport (who has written about PK in his books) might be the most provocative lens to apply to Personal Kanban, because his critique is deep: most productivity systems, he argues, are elaborate infrastructure for managing stuff to do (shallow work) while the cognitively demanding stuff (deep work) goes unscheduled and unprotected.

Newport would look at a kanban board covered in tasks…emails to send, forms to fill, meetings to schedule…and ask: where is the deep work? Even more likely is he’d say, why bother with all this? Where is the two-hour block for writing the proposal, designing the architecture, or thinking through the strategy? If it isn’t on the board (and the calendar) with a protected time slot, it isn’t happening.

His concern isn’t unfounded. It’s easy to feel productive moving cards across columns while avoiding the hard cognitive work that doesn’t break into neat tasks. The Personal Kanban blog tackled this directly in Tonianne’s piece How to Stay Focused In a World Full of Distractions, which explores the neurological cost of context-switching. Newport calls the goo of switching “attention residue” and it lingers when you jump between tasks.

But here’s where Newport and Personal Kanban find common ground: WIP limits. Newport’s deep work philosophy is essentially a WIP limit applied to your cognitive capacity. When the Personal Kanban blog examined Focus: Why Limit Your WIP, we came at the same principle from a different direction…you can’t do deep work if you’re carrying seven tasks in your head simultaneously. (You can also engage in Pomodoros to have protected focused time…we’ll detail that in a later post.)

PK and Deep Work: use your kanban board not just to track what you’re doing, but to protect what you need to think about. A card that says “Deep Work: Q3 Strategy (2 hrs)” sitting in your Doing column, with a WIP limit that prevents anything else from crowding in beside it, is Newport’s philosophy made visible.

The Focus of This Lens: A PK board can either enable or destroy deep work depending on how you use it. If every card is a 15-minute task, you’ve built a context-switching machine. If you use WIP limits to protect sustained cognitive effort, you’ve built a deep work fortress.

Lens 4: Taiichi Ohno Says You Are Wasting Your Time

Taiichi Ohno was the father of the Toyota Production System and the person who invented the kanban method in manufacturing. He didn’t deal much with individual work but he would have had a unique perspective on Personal Kanban. He’d hopefully see a direct descendant of his system. (But he might not be entirely pleased with how it’s been domesticated.)

Ohno’s kanban wasn’t a feel-good visualization tool. It is a ruthless waste-elimination system. In Toyota’s factories, kanban cards were signals that control the flow of production. You can only produce what the next station pulled, and only when it pulled. The entire point was to make waste visible so you could destroy it. And to make sure that every yen Toyota spent was creating value.

He identified many kinds of waste, but one he considered particularly destructive was overproduction…doing more than what’s needed. In personal work, you live overproduction every day: saying yes to every request, starting projects before finishing others, gold-plating work that needs to be good enough, and maintaining commitments that no longer serve any purpose.

Ohno would insist that WIP limits are structural constraints that reveal problems. Not nice to haves. If you have a PK without any WIP limits, your work-car has 2 tires. When your WIP limit forces you to stop starting new work, it makes bottlenecks visible. Maybe you discover that three of your five in-progress items are blocked waiting for someone else. That’s not a task management problem — that’s a process problem. And you’d never have seen it if you’d let yourself keep pulling new work to stay busy.

The pull system is Ohno’s deepest contribution to personal productivity. Most people push work: they look at the backlog and ask “what should I do next?” Ohno’s system pulls: you only start new work when you have capacity, as signaled by finishing something else. The difference sounds semantic. In practice, it’s the difference between a system that creates overload and one that prevents it.

The Focus of This Lens: Personal Kanban’s power comes from its manufacturing DNA, from its focused heritage. WIP limits, pull systems, and visual management aren’t productivity hacks, they’re proven engineering principles applied to knowledge work. Ohno would say: stop treating your board as a to-do list and start treating it as a production system. Then ask where the waste is.

Lens 5: Csikszentmihalyi and PK Flow

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi spent decades studying the moments when people are most alive… in states he called “flow.” Not productivity, not efficiency, not output. The state where you’re so absorbed in what you’re doing that time distorts, self-consciousness dissolves, and the work itself becomes the reward. Where productivity, effectiveness, and output become effortless.

Flow isn’t random. Csikszentmihalyi identified its prerequisites: clear goals (you know what you’re trying to do), immediate feedback (you can tell whether you’re doing it well), and a match between challenge and skill (hard enough to engage you, not so hard you shut down).

We designed PK so that a well-designed kanban board provides all three, because this is how you achieve the goals of the other five lenses. Everything rests in having the clarity to do the right work at the right time with the right people. To act with confidence.

Clear goals? Every card states what needs doing.

Immediate feedback? Moving a card to Done, or seeing it stuck in Doing, gives you instant information about your work.

Challenge-skill balance? That’s what WIP limits create.

By constraining how much you take on, you prevent the overwhelm that pushes challenge past your skill threshold and kills flow.

His tension with David Allen is interesting and helps us select work and build out how we work. GTD requires regular system maintenance (weekly reviews, inbox processing, context switching between lists). Csikszentmihalyi would warn that all of this meta-work interrupts the very state that makes work meaningful. You can’t be in flow while reviewing your Someday/Maybe list. The system that enables good work can also prevent it.

Tonianne and I explored this territory in pieces about working intentionally and discovering your flow through design patterns. The “Thinking Ticket” in Toni’s post was a card one of our clients used on her board specifically for reflection and cognitive processing. It was a beautiful example of resolving this tension. It makes meta-work part of the flow rather than an interruption to it. So you can Cal Newport a bit here as well.

The Focus of This Lens: The ultimate purpose of any productivity system is creating the conditions where work feels clear and meaningful. Kanban’s visual feedback and WIP limits don’t just help you get more done. They help you get into the state where doing feels like being.

Where the Lenses Collide — and What the Collisions Teach Us

The five frameworks don’t converge neatly. They argue. And the arguments are awesome.

Allen wants you to capture everything. Newport wants you to eliminate the shallow. Both are right. The resolution: capture everything once (Allen), then ruthlessly filter before it reaches your board (Newport). Your backlog is a holding pen, not a commitment. The GTD-Kanban hybrid approach turns this from theory into practice.

Covey starts with values. Ohno starts with waste. Top-down meets bottom-up. The resolution: use Covey’s quadrants to decide what deserves to be on your board, then use Ohno’s pull system to control how it flows through. Values tell you what to work on. Lean tells you how to work on it without creating more problems than you solve.

Csikszentmihalyi needs immersion. Allen needs system maintenance. The resolution: schedule your review as its own flow activity, not as an interruption. The weekly review isn’t overhead … it cannot be. This is the practice that makes every other practice possible. Give it a card. Give it a time block. Make it part of the work, not work about the work.

Newport designs the environment. Csikszentmihalyi cultivates the internal state. Both matter. WIP limits are environmental design (Newport). The clarity and absorption they create is internal state (Csikszentmihalyi). The board is the bridge between the two…an external structure that produces an internal experience.

All models are wrong, some are useful…but none of them are an island. No model is sacred.

What a Five-Lens Board Looks Like

If you took one practical insight from each thinker and built them into your Personal Kanban practice:

From Allen: Review and Focus: Process your backlog weekly. Every card gets a next action or gets removed. No vague intentions.

From Covey: Select with Intention: Before pulling work, ask: is this Quadrant II? If your board has no important-but-not-urgent work on it, your board is lying to you about your priorities.

From Newport: Don’t Swim in Shallow Water: Include at least one deep work card per day. Set a WIP limit that protects it from being crowded out by shallow tasks.

From Ohno: Don’t Be Your Own Bottleneck: Respect your WIP limits absolutely. When you hit the limit, finish something before starting anything new. Investigate bottlenecks instead of working around them.

From Csikszentmihalyi: Your Production Should Be Healthy: Notice when you’re in flow and study what made it possible. Redesign your board to create those conditions more often.

Two rules. Five lenses. A deeper system.

Personal Kanban was created by Jim Benson and Tonianne DeMaria Barry, authors of Personal Kanban: Mapping Work | Navigating Life. Explore 15+ years of design patterns, primers, and practitioner insights at personalkanban.com.